|

| November 29, 2022 | Volume 18 Issue 44 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

60 years ago: First microgravity experiment flown on Project Mercury investigates liquid propellant behavior

In 1961, Project Mercury Astronaut Scott Carpenter underwent a simulated mission in the procedures trainer at Langley Research Center, which at the time was headquarters for NASA's manned spacecraft operations. [Credits: NASA]

By Robert S. Arrighi, NASA Glenn Research Center

At 7:45 a.m. on May 24, 1962, Scott Carpenter's Mercury-Atlas Aurora 7 lifted off from Cape Canaveral, FL. Five minutes and 26 seconds later, a small amount of dyed liquid flowed into an encapsulated glass tube behind his right shoulder as the capsule entered space. The experiment, designed by researchers at NASA Lewis Research Center (now NASA Glenn), provided the nation's first long-duration study of fluid physics in a microgravity environment.

The three-Earth-orbit mission, the fourth crewed flight of Project Mercury, was piloted by astronaut Carpenter, the sixth human to fly in space.

The low-gravity environment of space posed a number of questions for engineers during the early years of the space program. While much of the focus was on its effect on humans, researchers at NASA Lewis were more concerned about how liquid propellants would react.

Lewis was responsible for the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants that would fuel the Centaur and Saturn upper-stage rockets. Their researchers did not know how the fluids would settle in the tank without gravity. Pumping the propellants would be difficult if the fluid separated into blobs or pooled along the walls.

Photo of Lewis-designed microgravity experiment as it was prepared for launch on the Aurora 7 mission. [Credits: NASA]

The center created a group to study the issue and designed a variety of methods to produce brief periods of microgravity. These included the ground-based 12.5-foot counterweight rig in 1958 and 2.2-Second Drop Tower in 1960, as well as airborne tools that produced slightly longer periods of low gravity, such as AJ-2 Savage aircraft and sounding rockets.

The early testing indicated that microgravity produced a random distribution of the fluids in the tank, but the placement of a cylindrical tube or baffle in the center could draw the liquid in and direct it to an outlet port. The researchers, however, needed longer periods of low gravity to confirm their ideas. In addition, they sought to determine if spacecraft accelerations or in-flight disturbances would disrupt the process.

NASA's Space Task Group agreed to include a fluids microgravity experiment on the Aurora 7 mission planned for the spring of 1962. Lewis researchers Donald Petrash, Ralph Nussle, and Edward Otto designed a test package that consisted of a 1.1-inch cylindrical baffle inside a glass ball filled 20% full of dyed water. The container was placed in a metal frame and affixed on the capsule wall next to Carpenter's helmet.

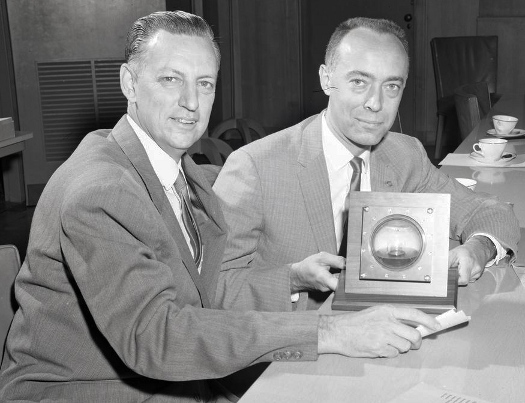

Cary Nettles, head of the Fluid System Dynamics Branch (left), and Warren Plohr of the Space Experiments Section examine the Lewis microgravity experiment before it was flown on the Aurora 7 mission. [Credits: NASA]

Although the experiment did not require any human interaction, Carpenter reported during his third and final orbit that the fluid had completely filled the baffle. The in-flight astronaut observation camera verified Carpenter's visual report and revealed, with the exception of a brief interruption during firing of the retrorockets, that the fluid remained in the tube throughout the capsule's roughly four and a half hours in space.

The Lewis experiment was significant in that it confirmed predictions that the tube provided sufficient surface tension to stabilize the liquid and, perhaps more importantly, demonstrated that neither spacecraft movement nor change of speed had any significant effect on the liquid's position.

Since that first in-space test in 1962, the center has conducted hundreds of microgravity experiments on board the shuttle and space station. The studies have expanded and include combustion, biotechnology, and materials science, as well as fluid physics.

Read more interesting NASA history articles at nasa.gov/topics/history/index.html.

Published November 2022

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy